A Favorable Human Rebirth

These teachings on the eight conditions most conducive to practicing Dharma are excerpted from Chapter 4 of Lama Zopa Rinpoche's book The Perfect Human Rebirth: Freedom and Richness on the Path to Enlightenment, edited by Gordon McDougall. The teachings in this book are drawn from Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s graduated path to enlightenment (lamrim) teachings given over a four-decade period, starting from the early 1970s.

One result whose cause we can create with this perfect human rebirth is another human body suitable for practicing Dharma. Ideally, such a rebirth has eight ripened qualities, as mentioned by Pabongka Dechen Nyingpo in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand.1 These are eight conditions most conducive to practicing Dharma:

- A long life

- A handsome or beautiful body

- A noble caste

- Wealth

- Power and fame

- Trustworthy speech

- A male body

- A strong body and mind

Each of these qualities makes practicing Dharma that much easier, so we should do our best to cultivate them.

The first is to have a long life. If we spend our life chasing worldly happiness, then no matter how long we live it will be totally wasted. The longer we live, the more we will harm others, and when we die we will experience great suffering. A long life gives us more time to practice Dharma and thus derive greater benefit from our perfect human rebirth.

The second ripened quality, a handsome or beautiful body, gives us the power to attract and influence others and thereby be of more benefit to them.

The third ripened quality, a high or noble caste, might sound a bit strange to Westerners, but even today in India and Nepal people’s caste is important and determines their social standing. The purpose for wanting to be of noble caste is not for the wealth it often brings (there are also many poor high caste people in India) but for the respect that others show those of higher caste. This is not to have a good reputation for its own sake but because it is easier to influence people if they respect us, and as our job is to benefit others as much as possible, it is that much easier when we have their respect.

Even in the West, if somebody is a butcher, for instance, a job involved in killing, people see that person as somebody creating negative karma and therefore not a good influence. And so, in India and Nepal, high caste people command respect. The great teachers like Shakyamuni Buddha and Lama Atisha chose to be born into high caste families so that many people would listen to and be benefited by them. By giving up all the wealth and power of the noble lives they led and devoting their lives to practicing the Dharma, both the Buddha and Lama Atisha were giving us teachings by example. Seeing a beggar meditating doesn’t inspire us to meditate, but when somebody like a king, who has wealth and power, begins to meditate, millions of people are inspired to try to meditate too.

The West does not have a caste system as such but still we are influenced by the rich and famous. Celebrities like Richard Gere, for example, are known to young and old, and people try to emulate the way they dress and the way they live. They become examples for worldly people. If that example is a good one, then they become a very powerful positive influence.

In the same way, the next two qualities, wealth and power and fame, are not for worldly pleasure but for the ability they give us to influence others and bring them into the Dharma. A king or a dictator has a huge influence over the people he controls. Mao Zedong ruled China as head of the Communist Party for many years, telling people what to do and how to think. His influence caused millions of people to suffer. The mistake the Chinese people made was to not analyze his philosophy, to not check what he said, but to just follow him blindly because of the great power and fame he had. Because of that he could control the army and the people.

The sixth quality is having trustworthy speech. That means people trust us and our words have weight. His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the perfect example of this. With just a few words he can have a very positive impact on people’s minds. We can explain the same thing in great detail and numerous times and nobody will listen, but when somebody like His Holiness simply mentions it briefly, everybody listens. Every word he utters has the power to benefit other sentient beings extensively.

If we want to be able to influence people verbally in the same way we must create the causes of trustworthy speech. Just as a wife won’t listen to an untrustworthy husband, if our words don’t have power, other people won’t listen to us. To be able to influence others—even a few, let alone thousands—we need to create those causes. Whatever we say to others, our main aim should always be to bring them into the path to enlightenment.

The seventh point, having a male body, often causes Western students some consternation. We don’t need a male body to achieve enlightenment; both men and women are equally able to achieve enlightenment and there is nowhere in Buddhism that says otherwise.

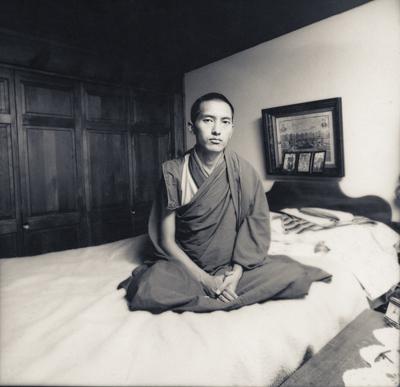

I remember a long time ago in Root Institute in Bodhgaya, the question of why a male body was important was put to Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche2 by Venerable Karin, the wonderful Karin, the pillar of Kopan monastery, who always stays at Kopan, never going anywhere or needing anything.3 The question and answer were translated by Venerable Tsenla, Yangsi Rinpoche’s sister,4 who helped found the Kopan Nunnery5 and who has done incredible work for decades. She is Tibetan, but even so I sensed she was a little disturbed by what Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche had said. Rinpoche did not answer directly but asked instead why there were so many more male leaders in the world than female ones.

This quality relates to overcoming obstacles in the outside world, although I think it can also relate to which kind of body has the most obstacles. Even though there are more and more female heads of state emerging these days, there are still far more male leaders, but that has no bearing on the qualities of the women.

The texts mention that it depends on the form—male or female—in which a person wants to benefit other sentient beings. There is no difference in the potential of either sex; both men and women can attain enlightenment in exactly the same way. If a man doesn’t practice Dharma, nothing happens, and it’s the same for a woman. Just as there have been innumerable male yogis who have gone on to attain enlightenment, there have also been innumerable yoginis who have done the same thing. Tara is probably the most prominent example of a person who attained enlightenment in female form. So why do we count having a male body as an advantage? Every day, many people do Tara or Vajrayogini practice and gain incredible benefit from it. There is also Machig Labdrön6 who spread the practice of chöd in Tibet. This is a quick way to realize emptiness, a hero’s bodhicitta practice on exchanging self with others by totally making charity of one’s whole body to others. Often performed in a terrifying place like a charnel ground, practitioners transform their flesh and bones into nectar and offer it to the Three Jewels and the sentient beings of the six realms, particularly the spirits.

So, there are many practitioners who have become enlightened in female aspect. It depends on our own motivation. If we see that we can benefit others more in a female body than a male one, we can ensure that we get one. And vice versa, of course.

The English nun, Venerable Tenzin Palmo, is a great inspiration. Like the wonderful stories we hear of French and Spanish Christian nuns living in isolated places or the great Tibetan yoginis, she lived in an extremely remote place for twelve years, sacrificing her life to the practice and facing great hardships. We need inspiring stories like that.7 To get results from our practice, the main thing we need is continual renunciation, so examples like hers are very, very good. Just as the places in India and Nepal where yogis achieved the path hundreds of years ago are to this day places that inspire others to practice, by being a living example, she is an inspiration to the Western world.

The last ripened aspect is having a strong and healthy body and mind. Some translate it as “powerful body.” When we are sick, we can’t function properly, don’t think clearly and have no space to think of others. It also means having a body and mind that are strong and resilient enough to withstand the hardships that can come with Dharma practice.

Milarepa is the perfect example of this. He had an incredibly strong mind, with iron-clad determination. Nothing could deter him from practicing Dharma every second of the day. And with that, he put up with starvation and intense cold. He lived in conditions we could not even imagine. Though his body was stick-thin and blue-green from the cold and his diet of nettles, he developed an amazing resilience and was able to withstand any condition. Through his devotion to the Dharma he vanquished all thoughts of comfort and the other eight worldly dharmas.

In addition to the eight ripened qualities, a favorable rebirth also includes the four Mahayana Dharma wheels: relying on holy beings, abiding in a harmonious environment, having supportive family and friends and collecting merit and making prayers.

We need a Mahayana virtuous friend to guide us, the support of family and friends and a conducive environment. That does not simply mean meditating in a place where we are not liable to be harmed or get sick, as mentioned in the instructions for a calm-abiding retreat, but also that where we live—the place, our family and so forth—are harmonious and supportive of our Dharma practice. Collecting merit and making prayers seems very obvious to me. Of course we need to do that.

Notes

1 Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, pp. 414–419. [Return to text]

2 Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche (1926–2006) was a highly respected ascetic yogi who lived in Dharamsala and was a guru of Lama Zopa Rinpoche. He was one of the great proponents of the Kalachakra tantra. [Return to text]

3 Ven. Karin Valham, a Swedish nun who first attended the seventh Kopan course in 1974 and was ordained in 1976. She has been Kopan’s resident teacher since 1987. [Return to text]

4 Yangsi Rinpoche (b. 1968), a lharampa geshe from Sera Je Monastery in south India, became the director and resident teacher of Maitripa College in Portland, Oregon, at its inception in 2006. His sister, Ven. Tsenla, is a well-known and much sought after interpreter, having learned excellent English at a school in Darjeeling. [Return to text]

5 Khachoe Ghakyil Ling, founded next to Kopan in the 1980s, is now the largest nunnery in Nepal and home to more than 400 nuns. [Return to text]

6 Machig Labdrön (1055–1149), literally “Unique Mother Torch of Lab,” was a great tantric practitioner and teacher who developed several chöd practices. [Return to text]

7 See Cave in the Snow for Ven. Tenzin Palmo’s story. [Return to text]